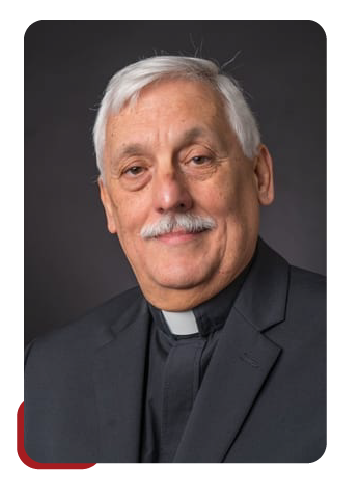

Father General Invitation - Assembly IAJU 2025

The Jesuit University: Witness to Hope, Creative and Dialogical Presence

Charism. Context. Way. I would like to start these reflections not with what we do but with who we are. I will not begin by looking at the world around us and asking how best to respond to its needs. Instead, I want to begin by recalling our identity, the charism that we have received as a gift of the Holy Spirit. Conscious of our identity, we can then contemplate our context and discern how to walk toward a more reconciled and just world, living now as though we were already in that new world. We place ourselves in the present as witnesses to hope in universities that are apostolic, marked by solidarity, creative, and dialogical. That is our way. That is the path forward.

Fidelity to the task to which we have been called in the universities of the Society of Jesus requires, as a conditio sine qua non, deep rootedness in the identity that flows from our charism. This charism defines our contribution to the mission of the Lord Jesus —the crucified-risen one— the mission entrusted to the community of his followers, to the Church walking in every corner of the world.

The Charism: Rooted in Our Identity

As he finished writing the Constitutions of the Society of Jesus at the behest of the founding companions, Ignatius of Loyola asked himself: How will this whole body be preserved and increased in its well-being? We, too, ask ourselves day by day how it will be possible to maintain, grow, and enhance the university apostolate, inspired by the commitment to contribute to justice and reconciliation in order to heal the open wounds of humanity today.

The answer offered by the Ignatian text takes us directly to the origin of our identity. “The Society of Jesus, which has not been instituted by human means, cannot be preserved or increased by them, but by the grace of the omnipotent hand of Christ our God and our Lord. Therefore, in Him alone must be placed the hope that He will preserve and carry forward what He deigned to begin for His service and praise and for the aid of souls.” 1

Being convinced that we are here at God's initiative, not ours, is key. Recognizing the Lord's initiative, we avoid anxiety in situations of adversity or pride in moments of apparent tranquillity, when we enjoy success and recognition. It is the Lord who takes the initiative. He invites us to take part in his work, a work that is full of risks.

The Fourth Gospel describes in detail the Passover meal that precedes the arrest, passion and crucifixion of Jesus. 2 It begins with the challenging gesture of the Master who takes the initiative, washes the feet of each of the disciples, and proposes that they follow his example in service to the others. In that setting, he reminds them that they are his friends because he has chosen them and revealed to them both the true face of God the Father-Mother and the way to reach God. 3 Love is the source of the identity of the university apostolate of the Society of Jesus. Jesus of Nazareth reveals the love on which the possibility of a truly human life is founded. In handing over his life, he showed the way to the reconciliation that leads to fraternity among all human beings. The university apostolate makes sense when it contributes to opening up and following the path of justice and reconciliation that leads to fraternity.

The commitment of each of us to the university apostolate finds fulfilment and meaning to the extent that we acknowledge that it was God who inspired this apostolate at its beginning, and it is God who sustains those on whose shoulders it is carried forward.

Hope sustains personal and collective commitment to a complex task like university management. Because we live with hope, we are able to see that what appears to the ordinary eye to be impossible, is possible when we allow the love of God to work in human life. Of course, to place all our hope in him means more than believing that what looks impossible is possible. It means living already, now, as we hope that the life of all will be. The one who has hope not only has faith that another world is possible but behaves as if already living in it.

That is what Jesus showed when he did not hold onto the privileges of being God but become "one more" among human beings, learning with suffering to do God's will. 4 The incarnation of God in the human being Jesus leads to recognition of the constitutive fragility of our persons and our institutions.

Political situations, economic difficulties, and personal, familial, and institutional fears generate uncertainty and provoke emotions that are difficult to handle. Faced with this uncertainty, we need to recognize fragility as a dimension of our life. By acknowledging fragility, we are able to keep uncertainty and fear from taking control over our personal and institutional life. We place our hope in God alone.

Our identity invites us to see as God sees, which is to see through the eyes of those who suffer injustice. From there that we can perceive how the Lord is acting in history. Let me turn again to the Gospels. The parable of the sower sheds light on the identity of a university under the responsibility of the Society of Jesus. 5 The university scatters seed on and off campus. It plants the best seed it has. However, the seed falls on different types of ground and produces fruit, or not, depending on the quality of the soil where it falls. The identity of the universities under the responsibility of the Society of Jesus guarantees the quality of the seed that is sown and drive not stop sowing it.

The Gospel of Mark offers us other parables to broaden our understanding of the role of the university. The quality of what we preach – a world in which every human being can live with dignity – is a small seed, like the mustard seed, but it grows until it becomes a tree giving space for the life of others. The sower must scatter the seed; he does not make it grow, but he knows that if he does not sow it, there will be no fruit.6

The Society of Jesus understands its apostolate as collaboration in the mission of reconciliation, contributing to the struggle for social justice. Reconciliation is a complex task. It requires achieving peace among peoples. It seeks fraternity as a defining feature of social life. It requires halting the deterioration of the environment and restoring relationships with nature to care well for the earth as a common home. It also aspires to reconciliation with God, realizing the dream of the fullness of life that springs from limitless love.

The identity that brings us together in this IAJU Assembly invites us to be open to action of the Spirit who makes all things new, setting aside fear of the convulsions that are characteristic of human history, especially in times of epochal change. 7

It is equally important to remember that Jesus did not offer his followers a trouble-free life, but exactly the opposite: “Go, I am sending you out like sheep among wolves... Look, I have given you power to trample snakes and scorpions and to overcome all the strength of the enemy, and nothing will harm you. Yet do not rejoice that the spirits submit to you, but that your names are written in heaven.” 8 And again: “Remember what I told you: A servant is not greater than his master. If they have persecuted me, they will persecute you, too.” 9

Keeping our hope firm while living in difficult times requires strengthening the identity of all members of the university community. A university community rooted in shared identity is better able to successfully confront the difficulties that hinder its mission.

The Context: Sharpening Our Political Sense

To take these reflections a step further, I call to mind another Gospel parable: “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to someone who sowed good seed in his field; but while everybody was asleep, an enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat, and then went away. So, when the plants came up and bore grain, then the weeds appeared as well. And the slaves of the householder came and said to him, ‘Master, did you not sow good seed in your field? Where, then, did these weeds come from?’ He answered, ‘An enemy has done this.’ The slaves said to him, ‘Then do you want us to go and gather them?’ But he replied, ‘No; for in gathering the weeds you would uproot the wheat along with them. Let both of them grow together until the harvest; and at harvest time I will tell the reapers, Collect the weeds first and bind them in bundles to be burned, but gather the wheat into my barn.” 10

An awareness is growing that humanity is living through a profound change of epoch. The consequences of this change sometimes take us by surprise. We must humbly recognize the inadequacy of our intellectual tools for measuring the effects of epochal change, understanding the present, and visualizing the future. Uncertainty is gaining ground in personal and social life. Uncertainty then sparks fear, provoking defensive reactions that turn our gaze toward an idealized past that never really existed. Fear tempts us to reject the newness of our time.

On every continent, social and political processes are creating adverse conditions for our apostolates. International trends make processes of justice and peace more and more an uphill climb. A few years ago, Moisés Naim published11an analysis of the trends that threaten democracy in the world. He called them the three Ps: populism, polarization and post-truth. The three Ps serve the disordered lust for power of groups whose particular interests are at odds with the common good of humanity and the planet. Recently we have seen the rise of nationalist proposals and ideologies that favor closed borders and the expulsion of immigrants. Policies protecting national economic activities are proliferating. We can, therefore, add a fourth P: protectionism. Step by step, these trends are gaining ground and even gathering growing electoral support in many countries.

The reflection of the IAJU over the years and in this assembly highlights several fundamental aspects of the critical situation that we face at this time in history. We face a worrisome weakening of democracy, even in countries with a long democratic tradition. We also recognize the diminishing influence of the international institutions that were created to uphold and advance human rights, social justice and citizen participation in decisions that affect the common good of humanity.

Reviewing this situation could leave us feeling overwhelmed. Uncertainty can turn into anxiety that paralyzes action. That would serve the purposes of those who seek to weaken citizen participation in public life, to weaken democratic rule to the point of rendering it inoffensive, and to undermine the civic culture of the people. However, when we confront this situation in the hope that strengthens us, uncertainty can be experienced as an opportunity, a chance to contribute to changing the course imposed by those who feel themselves to be in charge today.

As we come together here, we renew our pledge to be bridges that support intercultural dialogue, to defend the rights of migrants and refugees, and to consolidate our interconnectedness as members of one human family. We renew our commitment to form universal citizens, citizens who recognize the priority of the universal common good over the particular interests of nations, no matter how powerful those nations may be or how eager they are to exercise their imperialist vocation.

As participants in global networks, our institutions are uniquely positioned to counter current trends. They can strengthen international associations. They can expand the sense of global citizenship among our faculty, staff, students, and alumni. They can reinforce a culture of solidarity in our educational mission, especially among institutions that share the same identity and apostolic purposes. We must promote inclusive economic models and advocate for public policies based on solidarity, sustainability and global justice.

Probably the most urgent and existential threat of our time is the ecological crisis. We are facing a planetary emergency. Accelerating climate change, catastrophic loss of biodiversity, widespread pollution, and unsustainable systems of production and consumption are pushing to their limits the earth's ecosystems and the human communities that depend on them. Far from helping to address the environmental crisis, the current context of war, authoritarianism, anti-democratic policies and economic instability aggravates it, diverting national and international political agendas from socio-ecological concerns.

As we gratefully remember Pope Francis, we are invited to commit to putting into practice the challenge prophetically expressed in Laudato Si' and Laudate Deum. This is not only a scientific or political matter; it is profoundly moral and spiritual. It touches our understanding of our place in the world and our responsibility to future generations. In this context, the universities of the Society of Jesus associated in the IAJU should reaffirm their commitment to be prophetic voices and proactive agents in the movement toward ecological conversion. This will require more than sustainability offices or specialized research programs. It demands integrating care for our common home into all dimensions of university life, including curricula, operations, community engagement, and student formation.

We commit ourselves to the education of ecological citizens, men and women capable of establishing correct relationships with nature, with others and with themselves. To this end, we must promote interdisciplinary thinking that links sciences and humanities, ethics and economics, spirituality and social action. The hope that inspires us will give us the necessary courage and depth of thought and action to use our best resources to contribute to overcoming the ecological crisis. The ecological crisis demands depth, courage and hope.

On previous occasions, we have analysed the radical change that is taking place in the production and transmission of knowledge with exponential advances in digital technology, especially in artificial intelligence (AI). AI is redefining industries, professions, social structures, and work itself. It also raises profound ethical, anthropological, and spiritual questions: What does it mean to be human in an age of intelligent machines? How should we understand moral agency, responsibility, and discernment in this new environment?

This is not merely a technical challenge; it affects the core of what we do as universities. AI not only transforms how we conduct research, create knowledge, and teach. AI also impacts why we do what we do. Are we capable of educating individuals who can navigate a world shaped by these technologies with wisdom and responsibility? Are we ensuring that AI serves humanity and does not become a tool of dehumanization?

Our identity requires us to contribute to an ethical, humanistic and spiritual vision of the digital future. We need to create spaces of critical dialogue with technological advances, giving clear priority to human dignity, justice, and the pursuit of the common good. This entails promoting a critical digital literacy, cultivating an ethic of care and responsibility in the design and use of technologies, and educating professionals aware of the human and social consequences of their work.

We must also renew the dialogue between science and faith, between reason and spirituality, at a time when the authority of scientific knowledge is questioned and conspiracy theories, fake news and scepticism about the truth take hold. Our universities have a duty to strengthen critical thinking, the rigorous pursuit of truth, and intellectual discernment as part of integral formation.

In my message to the founding assembly of the IAJU (Bilbao, 2018), I emphasized that the intellectual apostolate undertaken in our universities must sharpen our political sense and give us the wisdom that comes from discernment. Discernment is more than gathering and analysing data. Discernment develops the capacity to perceive where God is at work in the global and local situation in order to choose what better leads to the glory of God, which is nothing other than the fullness of human life. One of your tasks, as leaders of Jesuit universities, is to cultivate that sensitivity that leads to the wisdom of discernment—the capacity to view the world and historical events through the eyes of the Triune God.

To discern with the wisdom that goes beyond the data to perceive the action of God requires personal and collective qualities and capacities. I am speaking of a discernment in common that needs adequate space and time, as well as good information and openness to what is new, to what is not known or perceived at the beginning of the exercise.

Creating the conditions to make discernment in common an ordinary practice of the leadership teams of Jesuit universities is an excellent way to accompany both the decision-making process and the individuals who participate in it. I am aware of the difficulties of doing this, even in contexts of relative calm. For this reason, I often return to the moment when Jesus prayed in the Garden of Olives after the Last Supper12. The scene dramatically portrays the challenges of discernment in common ("could you not keep watch with me?"), the struggle with anxiety and the desire to flee (“take this cup away from me!”) and ultimately, the acceptance of reality, the peace of putting oneself in the hands of God.

On the Way: Creative Presence and Apostolic Solidarity

The first contribution of the institutions that share this Jesuit identity is to be present. We must be present in complex and difficult situations that disrupt daily life and weigh heavily on the people who are entrusted with university leadership. The presence must be creative rather than passive. To sustain an open university offering integral formation in the midst of great difficulties demands openness to innovation, to seeking and finding alternative ways to fulfill the university’s social function, to maintaining active engagement with different sectors of the society in which the university carries out its mission.

Solidarity is a constitutive element of this presence, because a Jesuit university is never alone. It belongs to the apostolic body of the Society of Jesus, embedded locally in each social context and connected globally with a universal vision. It forms part of the fabric of diverse local, regional and worldwide networks. Even beyond the university networks, the institution acts in partnership with other educational, spiritual, research and social action networks, including international organizations such as the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS).

This solidarity is apostolic, because the mutual support is motivated by the desire to contribute to the mission. It is a solidarity among persons sent to make present in every moment the good news of the gospel and our hope in the real possibility of fraternal human relations. Fraternal relations can be built on recognition of the dignity of each person, on social justice, on appreciation for cultural diversity as richness for all, on an orientation toward the common good including a vital equilibrium with the environment. This apostolic solidarity in mission is, at a first level, with the People of God, the Church on pilgrimage in every place and around the world, connected in a special way with the organizations of religious life and lay movements in communion with the bishops responsible for the Christian communities.

Apostolic solidarity is possible and necessary even where the world is increasingly secular and in cultures that are described as post-Christian. I refer to those societies, especially in the so-called Global North, in which religious language, institutions and traditions are increasingly irrelevant or even viewed with suspicion. This does not necessarily mean that people are less spiritual. It does mean that the frameworks of Christian faith do not manage to speak meaningfully to the experience of many people. In these societies, solidarity is still possible, particularly in the commitment to the defence of human rights, social transformation, civic participation, care for the common home, and universal fraternity.

In this context, solidarity requires that we rethink the way we present the richness of our spiritual heritage so that it echoes in the hearts of our contemporaries, not as an imposition but as an invitation to a living fount of meaning, courage, and love. The project requires intellectual depth, spiritual maturity, and cultural sensitivity. It supposes opening spaces where students and teachers—believers, seekers, and sceptics alike—can enter into honest dialogue, explore the ultimate questions, and find opportunities to experience the transforming power of the gospel.

The solidarity that characterizes the apostolic presence of the Jesuit universities is very broad. The identity of the universities also helps them to see, in everyday life, the fulfilment of the Lord’s consoling promise at the end of his earthly life to remain with us until the end of the world. 13 One of the fruits of this IAJU Assembly should be the awakening of the sense of apostolic solidarity in each of the participants, who come from such diverse contexts. Our solidarity, which extends to many social sectors, enables us to support one another in complex and sometimes very difficult situations, drawing on the hope that we share.

The identity that grounds our association resonates with the identity the university itself. Any university is a community whose purpose is to seek and to share the truth. It is a complex and intergenerational community that unites students, faculty, staff and alumni in this challenging endeavour. The Fourth Gospel, one of the springs that nourish our identity, reminds us: If you remain faithful to my word, you will truly be my disciples, you will know the truth and the truth will set you free. 14

The commitment to the truth is a fundamental dimension of the university's task. It is a commitment not to the defence of dogma but to the honest search for deeper understanding of all the dimensions of life. At the 2018 IAJU Assembly in Bilbao, I shared the following reflection: "A university under the responsibility of the Society of Jesus is therefore called to create. A creative capacity that is demonstrated above all in the ability to be ahead of its time, several steps ahead of the present moment. A university able to see beyond the present because it cultivates and is nourished by a historical memory that both inspires and illuminates.”

We know well that a university under the responsibility of the Society of Jesus is part of a humanistic tradition. Therefore, it seeks a deeper understanding of human truth in order to contribute as effectively as possible to reconciliation and universal fraternity. A rereading of Pope Francis's encyclical Fratelli tuttican shed light on the path to be followed by a university that lives its faith in the promotion of justice and reconciliation.

At the 2018 IAJU Assembly in Bilbao, I also recalled how Ignacio Ellacuría, S.J., one of the martyrs of the UCA-El Salvador, strongly insisted on understanding the university as a project of social transformation. Trying to explain the meaning of those words, I said: "It is a university that moves toward the margins of human history where it encounters those who are discarded by the dominant structures and powers. It is a university that opens its doors and windows to the margins of society. With them comes a new breath of life that makes efforts for social transformation a source of life and fulfilment."

One of the consequences of the profound transformations that we are experiencing in this change of epochs is the broadening and diversification of the margins of society and of the socially excluded men and women who live at the margins. A university of the Society of Jesus is called to discover and interact with the margins of society. As a plural space fostering dialogue and deep understanding of historical, personal, and intellectual processes, the university is a privileged space for the exercise of human freedom, freedom to seek and to find, through research and teaching, paths of social transformation. It is a space where the evangelical message of liberation can contribute to finding better paths toward new life in the midst of the uncertainties and hardships of the daily realities that exhaust so many men and women. It opens space for hope. 15

Dialogue is the characteristic method of the humanistic tradition of a university inspired by the charism of the Society of Jesus. In his encyclical Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis strongly affirms dialogue as the path toward concord among peoples and peace for humanity. His description matches our notion of university spaces. Pope Francis writes: “Approaching, speaking, listening, looking at, coming to know and understand one another, and to find common ground: all these things are summed up in the one word ‘dialogue.’ If we want to encounter and help one another, we have to dialogue. There is no need for me to stress the benefits of dialogue. I have only to think of what our world would be like without the patient dialogue of the many generous persons who keep families and communities together. Unlike disagreement and conflict, persistent and courageous dialogue does not make headlines, but quietly helps the world to live much better than we imagine.” 16

Dialogue supposes the creation and maintenance of plural spaces that guarantee, promote, and favor conditions for encounter. Dialogue is only possible among people who recognize each other. To recognize the other, whether a person or a group, is the indispensable condition for listening to what each of the participants in the encounter wants to freely share about their experiences and feelings, about how they understand the social processes and how they propose to walk toward the future.

Dialogue is a tool of reconciliation and negotiation to arrive at shared social decisions. If dialogue fails to find a path toward a shared life in which decisions can be taken for the common good, if it is nothing more than a series of unrelated monologues, then it is like a wheel that spins in the air without ever touching ground and moving forward. Over the past decades we have had many experiences of repeated monologues that never connect. These have occurred not only between actors in opposing positions of power but also within the ranks of both government and opposition forces.

And when dialogue is not possible? We may find ourselves in social or political contexts that block any attempt at dialogue. Such situations challenge us to persevere in our efforts to create the conditions necessary for dialogue. To persist in this effort requires serenity, patience, and clarity of purpose. As the conditions for dialogue are being established to open a path toward transformation, our creative and steadfast presence becomes a witness. The power of testimony is at the foundation of the identity of the Jesuit universities. Indeed, faith in the God of Life who raised Jesus from the dead—Jesus who, emptying himself, gave his life entirely unto death on the cross – is founded on the testimony of witnesses, of the people who experienced him as alive after he was placed in the tomb and who gave their own lives to confirm their testimony.17

The hope that inspires our lives and actions is the basis for our lasting witness to an acceptance of diversity and dialogue that prioritizes the common good and negotiates political decisions to contribute to a democratic and humane society.

Universities as Witnesses of Hope

Our identity calls us to be agents of hope, justice, dialogue, and reconciliation. These are distinctive marks of the universities of the Society of Jesus. The world does not need more fear or despair. When many are overwhelmed by the fear of losing everything, even life itself, or by a cynicism that twists the truth and a polarization that suffocates democracy, our universities must accompany our students and our societies with wisdom and hope, nurturing vision, resilience, and solidarity.

Student well-being is among the topics to be addressed at this Assembly. It is a vital concern for universities that, as an element of their identity, honor cura personalis as a distinctive characteristic of the pedagogy that promotes integral personal formation. To accompany young people requires more than providing psychological support, extracurricular activities, social service opportunities, and other dimensions of university life. For a Jesuit university, accompanying the young means forming students in hope, helping them to believe that a more just, peaceful, and sustainable world is possible, and encouraging them to play their role in building it.

This sort of accompaniment is possible if the university remains at the side of the excluded, those marginalized by poverty, race, migratory status, gender, or some other form of structural injustice. Our academic work, our advocacy, and our community life turn into voice and visibility for the forgotten.

In the face of these complex challenges, the future of Jesuit higher education depends on solid intellectual leaders and a committed faculty and staff. These men and women need not only to understand and accept our identity and mission but to embody them. Formation in the distinctive elements of the identity and mission of Jesuit higher education is not a luxury; it is a necessary condition for the long-term sustainability of the universities. I am deeply encouraged by emergence of numerous formation programs in our universities and networks. Initiatives that provide opportunities for formation in Ignatian identity and mission for trustees, directors, academic leaders, faculty and staff are essential steps.

However, we can go further by ensuring that all the members of our university communities, academics and non-academics, Jesuits and laypeople, have a chance to freely participate in these formative processes. We can also expand and share our programs by creating global platforms to share resources, insights, and collaborative initiatives. Let us take advantage of the potential of virtual learning and digital tools, including artificial intelligence, to extend the reach of our formation efforts into every corner of our institutions.

I want to conclude with a simple invitation: let us walk together into the future inspired by the magis—not seeking more of the same, but engaging the needs of our time with responses that are deeper, better discerned, more innovative and more transformative. Let us be witnesses of hope.

I hope that this Assembly will inspire each of you and each of your institutions to go forward with clarity, courage, and joy, founded on the rock of our identity, at the service of the mission of the Lord that has been entrusted to us. Let us deepen our collaboration as a worldwide body, reaffirm our commitment to the educational values of the Society of Jesus, and face the challenges of our time with courage and with the serenity that comes from knowing that we do not walk the road alone.

Thank you very much

Arturo Sosa, S.J.

Bogotà, July 1, 2025

1 Constitutions of the Society of Jesus, 812.

2 Jn 13-17.

3 Jn 15:9-17: 9As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you; abide in my love. 10 If you keep my commandments, you will abide in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commandments and abide in his love. 11 I have said these things to you so that my joy may be in you, and that your joy may be complete. 12 “This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. 13 No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. 14You are my friends if you do what I command you. 15 I do not call you servants any longer, because the servant does not know what the master is doing; but I have called you friends, because I have made known to you everything that I have heard from my Father. 16You did not choose me but I chose you. And I appointed you to go and bear fruit, fruit that will last, so that the Father will give you whatever you ask him in my name. 17 I am giving you these commands so that you may love one another.

4 Philip 2:5-11.

5 Mt 13:1-23

6 Mk 4:26-34.

7 This passage from the Letter to the Hebrews (10:32-39) in which the author places the Christian community in difficulty before the mirror of its own experience can be illuminating: Recall those earlier days when, after you had been enlightened, you endured a hard struggle with sufferings, sometimes being publicly exposed to abuse and persecution, and sometimes being partners with those so treated. For you had compassion for those who were in prison, and you cheerfully accepted the plundering of your possessions, knowing that you yourselves possessed something better and more lasting. Do not, therefore, abandon that confidence of yours; it brings a great reward. For you need endurance, so that when you have done the will of God, you may receive what was promised. For yet “in a very little while, the one who is coming will come and will not delay; but my righteous one will live by faith. My soul takes no pleasure in anyone who shrinks back.” But we are not among those who shrink back and so are lost, but among those who have faith and so are saved.

8 Lk 10:3-10, 17-20.

9 Jn 15:20 completed by Mt 16:2, 21-24-26. In the evening you say: the weather will be fine because the sky is red. In the morning they say: today it is sure to rain because the sky is dark red. They know how to distinguish the appearance of the sky and do not distinguish the signs of the times. […] From then on Jesus.

10 Mt 13:24-30.

11 The Revenge of Power: How Autocrats Are Reinventing Politics for the 21st Century, St. Martin’s Press, 2022.

12 Lk 22:39-46

13 Mt 28, 20.

14 Jn 8:32.

15 Cf. Sosa, A., The University Source of Reconciled Life, IAJU, Bilbao 2018.

16 Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, n. 198.

17 See 1 Cor 15:1-10